Active Investors

Active InvestorsIn the Martin Scorsese film, The Wolf of Wall Street, the senior broker at L.F. Rothschild, Mark Hanna, delivers broker training to Jordan Belfort over a cocaine and martini lunch. “The name of the game is to move the money from your client’s pocket into your pocket. Number one rule of Wall Street: I don’t care if you’re Warren Buffett or if you’re Jimmy Buffett, nobody knows if a stock is gonna go up, down, sideways or in [expletive deleted] circles, least of all stockbrokers. It’s all a fugazi… It’s a fake.” Hanna goes on to highlight the lack of fiduciary duty to clients when he explains how clients keep trading with the broker because the clients are addicted to the process of trading. Hanna further explains that a broker needs to keep coming up with “brilliant ideas” to keep clients’ money at the firm and clients will keep trading “again, again and again” because they are addicted. Meanwhile, the client thinks he is getting rich, but that is only on paper, while the broker takes home “cold hard cash” via commissions. “That’s incredible sir,” exclaims Belfort, “I can’t tell you how excited I am.” Hanna: “You should be.”

Of course, the excitement of the broker equates to the despair of the client. My purpose in writing this book is to show you how to avoid becoming a victim to either an unscrupulous broker or to your own self-destructive behavioral tendencies that draw you into speculating, more generally known as active investing. This better way to invest is simply passive investing with index funds.

This 12-Step Recovery Program for Active Investors will walk you through the land mines and pitfalls of active investing and show you a better way to invest. When you complete this 12-Step Program, you will understand the differences between speculating versus investing, and become aware of the emotional triggers that impact short-term decisions. You will also obtain an enlightening education on science-based and rules-based investing that may forever change the way you perceive how the stock market works. You will learn the hazards of speculation and the rewards of a disciplined investment strategy. The best part is that you can change your own investment behavior, which can lead to a more profitable and enjoyable life.

Emotions often override reason when it comes to investment decisions, leading to irrational and destructive behavior. The financial news media and Wall Street feed the fear, anxiety and other stressful emotions experienced by investors, resulting in less than favorable investment outcomes. This book will teach you how to hang on in the midst of market turmoil so you can earn the long-term returns of capitalism.

As you climb the 12 Steps illustrated in the following painting, you will abandon the gambling behaviors of the active investors located in the bottom right corner, ascend the stairs to claim your risk-appropriate portfolio (symbolized by the woman handing out colorful balls), and continue up to the balcony where individuals who have successfully completed their 12-Step Journey enjoy the tranquility of an “investing heaven.”

Stairway to Investing Heaven

Stairway to Investing Heaven

Watch Step 1 from the documentary film Index Funds: The 12-Step Recovery Program for Active Investors.

Active investing is a strategy investors use when trying to beat a market or appropriate benchmark. Active investors rely on speculation about short-term future market movements and ignore the lessons embedded in vast amounts of historical data. They commonly engage in picking stocks, times, managers or investment styles. As later steps demonstrate, active investors who claim the ability to outperform a market are in essence claiming to divine the future. When accurately measured, this is simply not possible. Surprisingly, the analytical techniques that active investors use are best described as qualitative or speculative, largely including predictions of future movements of stocks or the stock market. Bottom line, these methods prove self-defeating for active investors and actually lead them to underperform the very markets they seek to beat.

The first step in any 12-Step Program focuses on recognizing and admitting a problem exists. In this case, this means identifying the behaviors that define an active investor.

These include:

- Owning actively managed mutual funds

- Picking individual stocks

- Picking times to be in and out of the market

- Picking a fund manager based on recent performance

- Picking the next hot investment style

- Disregarding high taxes, fees and commissions

- Investing without considering risk

- Investing without a clear understanding of the value of long-term historical data

There are sharp contrasts between the behaviors of active and passive investors. Passive investors don’t try to pick stocks, times, managers or styles. Instead, they buy and hold globally diversified portfolios of passively managed funds. The term “passive” translates into less trading, more favorable tax consequences and lower fees and expenses than actively managed strategies.

A passively managed fund or index fund can be defined as a mutual or exchange-traded fund (ETF) with specific rules of construction that are adhered to regardless of market conditions. An index fund’s rules of construction clearly identify the type of companies suitable for the fund and the trading rules to implement the fund. Equity index funds would include groups of stocks with similar characteristics such as size, value, profitability and geographic location of a company. A group of stocks may include companies from the United States, international developed or emerging countries. Additional indexes within these markets may include segments such as small value, large value, small growth, large growth, real estate and fixed-income. Companies are purchased and held within the index fund when they meet specific index parameters and are sold when they move outside of those parameters. Think of an index fund as an investment utilizing rules-based investing.

Figure 1-1 illustrates the different characteristics between active and passive investing. Introduced in the early 1970’s, index fund investing has caught on, and for good reason. As the chart shows, index fund investors have fared better in returns and incurred lower taxes and turnover than active investors. They are also able to invest and relax.

Figure 1-11

Obsessively playing the stock market is recognized by Gamblers Anonymous as a form of gambling addiction. San Francisco clinical psychologist Paul Good developed a set of warning signs that may reveal whether an active investor is actually a compulsive gambler in disguise. Among them are a preoccupation with the financial media, borrowing to speculate (leverage), inability to cease or control trading activity and throwing good money after bad in order to break even.2 As the former head of the Gambling Disorders Clinic at Columbia University, Dr. Carlos Blanco has a lot of experience with gambling addicts, and he says one difference between obsessive active investors and chronic gamblers is the age in which the disease is most prevalent. Pathological gamblers are typically in their late teens and early 20’s while people who are addicted to speculating in the stock market are commonly in their 30’s and 40’s. According to Christopher Burn, a gambling therapist at U.K.-based Castle Craig Hospital, development of intensive evidence-based therapies to treat compulsive stock trading and online ‘day trading’ are poised to become two of the biggest behavioral health challenges in the decades ahead.

Behavioral finance is a field that studies the connection between investors’ emotions and their financial decisions. In The Little Book of Behavioral Investing: how not to be your own worst enemy,3 author James Montier talks about the importance of planning ahead to protect us from the “behavioral biases that drag down investment returns.” He highlights the need for investors to pre-commit to an investment strategy in order to avoid the pitfalls of emotional decisions.

In Your Money & Your Brain,4 financial writer Jason Zweig details evidence of the release of addiction-related dopamine in our brains when we anticipate big wins. “The dopamine rush we get from long shots is why we play the lotto, invest in IPOs, keep too much money in too few stocks, and invest with active portfolio managers instead of index funds,” Zweig states. “Our brains are wired to force us into forecasting; it is a biological imperative. In fact, humans are born with what I’ve come to call ‘the prediction addiction.’” Several researchers working in neuroeconomics, including Northwestern Medical School’s Hans Breiter, have identified a striking similarity between the brain’s reaction to cocaine and the prediction of financial rewards.5

Even wealthy individuals struggle with emotions management and investing discipline. A Barclay’s study6

found that 41% of high net worth investors wished they had more self-control over their investing decisions. The study concluded that emotional trading can cost an investor about 20% in returns over the 10-year period studied. Investors who prevented themselves from over-trading through specific strategies were on average 12% wealthier than those who did not use self-control mechanisms. These self-control strategies include minimizing time spent checking their portfolios or seeking advice prior to making a buy or sell decision.

Several behavioral biases that affect decisions may include:

- Overconfidence: People mistakenly believe they can outperform the market.

- Hindsight bias: Investors think past events were predictable and obvious and believe they should have known better, when in truth, news is what moves the markets, and past events could not have been predicted in advance.

- Familiarity bias: Investors invest only in stocks they know, which provides a false sense of security. An example may be a “legacy” stock that’s been passed down in a family through generations. Geographical bias also comes into play when investors choose stocks of companies headquartered in their state or region of residence, which can lead to undiversified investments.

- Regret avoidance: Investors vow to never repeat the same decision if it resulted in a previous loss or missed gain, not accepting that the future cannot be predicted.

- Self-attribution bias: Investors tend to take full credit for investment gains and blame outside factors for losses, wrongly attributing success to personal skill instead of luck.

- Extrapolation: Investors base decisions on recent market movements, assuming the perceived trend will repeat.

These behavioral biases cause investors to believe they have control in areas where they actually have little or none. A disciplined, rules-based investing approach involves the understanding of the factors we can and cannot control, planning ahead and not giving into emotions when making investment decisions.

Figure 1-2 depicts the roller coaster of emotions active investors experience. In the emotional cycle, they wait until they feel confident their selected investments are on a perceived upward trend; then they place their orders. But once prices have fallen, doubt sets in. When that doubt turns to fear, they often sell the investment, resulting in a loss.

Figure 1-2

In contrast, Figure 1-3 shows the relaxed emotions that indexers enjoy by accepting market randomness and relying on investing science instead of making decisions based on emotions. Passive investors invest regardless of market conditions, because they understand that short-term volatility is unpredictable. They know that succumbing to gut instincts and emotions undermines long-term wealth accumulation. They also know that news about capitalism is positive on average, but involves some stomach-churning volatility.

Figure 1-3

In order to regulate their risk, passive investors also engage in periodic rebalancing and are rewarded over time for their discipline. Figure 1-4 depicts the disciplined emotions and approach of “Rebalancers” who sell a portion of their funds that have grown beyond their target allocation and buy more of other funds to restore their target allocation. This is actually the opposite behavior of active investors, because rebalancers will sell a portion of their portfolio after it has gone up and buy more of those investments that have declined in order to maintain a target asset allocation. This strategy seems counter intuitive and can be emotionally difficult to implement. Rebalancing requires discipline and ensures that a portfolio will remain at a relatively constant level of risk.

Figure 1-4

The impact of emotional triggers on investor performance is a subject of much analysis. An annual study called the Quantitative Analysis of Investor Behavior (QAIB),7 which has been conducted by Dalbar since 1994, attempts to measure the impact of investor decisions to buy, sell and switch into and out of mutual funds. Each year the study has shown the average mutual fund investor earns significantly less than the actual mutual funds.

“No matter what the state of the mutual fund industry, boom or bust: Investment results are more dependent on investor behavior than on fund performance,” a recent QAIB concluded. The report issued in March 2020 reiterated this finding, concluding that poor investor behavior caused the average equity mutual fund investor to underperform the IFA SP 500 Index by 5.30% for the year 2019.

Honing in on the deleterious effects of performance chasing behavior, the QAIB found that mutual fund investors “who hold on to their investments have been more successful than those who try to time their investments.” The report has shown for the 20th time in as many years that “the average investor earns less — in many cases, much less — than mutual fund performance reports would suggest.”

Figure 1-5 illustrates the results of the 2019 Dalbar study, which includes a comparison of the returns of an average equity fund investor to the returns of the market from 2000 through 2019. Permitting their decisions to be driven by short term volatility, the average equity fund investor earned returns of only 4.25%, while a buy-and-hold investment in the IFA SP 500 Index returned 6.02%. An investment of $100,000 made in 2000 grew to $229,891 over the 20-year period for an average equity fund investor, while the same amount invested in the IFA SP 500 Index grew to $321,929. Even better, an investor who owned an all-equity, small value tilted, globally diversified index portfolio would have grown a $100,000 investment to $468,894. Clearly, investor behavior can have a far more negative impact on investments than investors realize.

Figure 1-5

The Great Mirror of Folly

The Great Mirror of Folly

The perils of active investing have been well chronicled throughout history. In fact, nearly 300 years ago, a Dutch pictorial book titled "Het Groote Tafereel der Dwaasheid," or "The Great Mirror of Folly" painstakingly portrayed the fates that befell investors who heavily speculated as the world's first major stock market crash unfolded.

In the late 1600s, stock exchanges were formed in Amsterdam, Paris and London to bring together buyers and sellers of shares, mostly in companies relating to trade, banking and insurance centered on maritime expansion in the East and West Indies and along the Mississippi River.

The "Tafereel" depicts the promise and ultimate financial devastation experienced by the many investors who became swept up in the allure of amassing quick fortunes in the stock market or "wind trade."

The book includes approximately 79 copper engravings that tell the tales of hope, hype, speculation and devastation. It represents stockbrokers as harlequins or sly foxes and investors as frantic and crazed gamblers. I recently discovered the "Tafereel", and asked Lala Ragimov to recreate a particularly poignant scene titled: "Monument Consecrated to Posterity in Memory of the Unbelievable Folly of the 20th Year of the 18th Century."

The scene depicts a street in Amsterdam that had erupted into a trading frenzy. At the Quinquenpoix coffee shop, overflow trading became the norm because the exchange had become too crowded with traders manically trading to gain quick wealth. At the scene's center, a cart is being pulled by characterizations of the bubble stocks of the time, including companies like the South Sea Company, the Dutch East Indies Company, and the West Indies Company, a banking company and an insurance company. Driving the cart is Lady Insanity, while the Goddess Fortuna floats above, dropping stock certificates littered with snakes, while the devil blows bubbles in the air. Meanwhile, Lady Fame slowly, but assuredly, leads the cart to one of three destinations: the hospital, the mad house, or the poor house.

I bring this important book and painting to light because they reveal that the same powerful lessons learned in 1720 are still being taught today to investors who speculate in the stock market.

Monument Consecrated to Posterity

Monument Consecrated to PosterityWhile active investors, or speculators, seek to outperform the markets, buyers and rebalancers of index funds seek to capture the returns of the global market in a low-cost and tax-efficient manner. Long-term passive index investors select funds that track defined asset class indexes. Regardless of market conditions, they stay the course and do not make investment decisions based on emotions or forecasts. Since a globally diversified portfolio of indexes has delivered returns of capitalism at a generous 11.00% annualized return over the last 93 years ending 2020, a wise investment strategy is to buy, hold, rebalance and glide path a portfolio that is globally diversified across many asset classes or indexes.8

Stock market returns are compensation for bearing risk. Higher expected returns require higher risk. Therefore, investors should take on as much risk as they have the capacity to hold — their risk capacity. One of the most effective ways to determine risk capacity is to examine five distinct dimensions: an investor’s time horizon and liquidity needs, investment knowledge, attitude toward risk, net income and net worth. This is explained more fully in Steps 10 and 11.

Over a decade ago, Vanguard coined the term “advisor’s alpha” as a measure of the value added by passive advisors who adhere to the principles of controlling costs, maintaining discipline and tax awareness. The breakdown of the advisor alpha set forth in Vanguard’s 2014 & 2018 studies are shown below in Figure 1-6.

Figure 1-6

Advisors who play an active role in emotions management can be referred to as “passive advisors.” These knowledgeable advisors help maximize investor success by providing the critical discipline required to combat emotional reactions like pulling out of the market the way so many did in the downturn that occurred in 2008 to early 2009. Passive advisors not only help to manage investors’ emotions, they are fiduciary stewards of their clients’ wealth.

Figure 1-7 is an internal analysis of the performance of 533 IFA clients who worked with our advisors for at least 11 years from January 1, 2008 through December 31, 2018. This period included the decline of equities during the global financial crisis of 2008 and early 2009. IFA considers this to be a difficult period because it includes a steep drop followed by a full recovery. Even though many of these clients had inception dates prior to Jan. 1, 2008, we chose this time period so that each investor would have experienced the same market conditions. For each of the 100 benchmark IFA Index Portfolios, our research team maintains monthly historical returns that can be used to benchmark clients’ time-weighted returns. IFA determined the annualized returns of the clients’ index portfolios and compared that to the annualized returns of the original IFA Index Portfolio that was recommended at the beginning of the client relationship. The clients were divided into three groups based on how closely they followed IFA’s advice.

The 209 clients that followed IFA’s advice and stayed within 9 risk levels of the original index portfolio recommendation (green bar) captured approximately 100% of the benchmark index returns. The 161 clients that chose to not follow IFA’s advice and self-direct their portfolio by increasing their risk level by more than 10 portfolios or decreasing their risk level by more than 25 portfolios (red bar) only captured approximately 78% of the original recommended benchmark returns.

Figure 1-7

Knowledgeable passive advisors help their clients stay invested and rebalance throughout market turbulence. Such behavior enables these investors to maximize their ability to capture returns and provides justification for the right advisor. Many investors are lured into do-it-yourself indexing through index funds and exchange-traded funds (ETFs). This is a step in the right direction, but without an advisor, I would estimate that those investors have not experienced the full value of passive indexing. Quality passive advisors offer valuable services, such as rebalancing, tax loss harvesting, a glide path strategy, and other wealth management tools that, in my experience, are rarely properly applied by do-it-yourself investors. Step 12 provides more information on these topics.

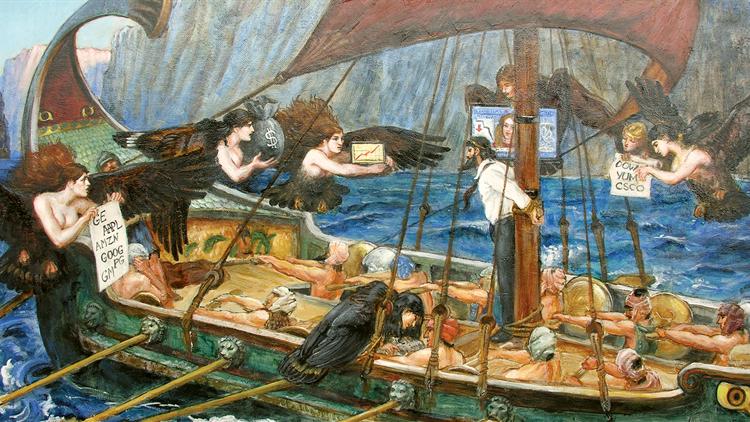

Homer’s legendary story about Ulysses (Greek name Odysseus) tying himself to the mast to avoid destruction can be aptly applied to investing. Ulysses was able to hear the alluring siren songs without being led to his demise, because he made an agreement with his seafaring crew as they approached the sirens. He ordered them to plug their ears with wax and keep him tied to the mast despite his protests and cries. Under no circumstances were they to untie him. Ulysses desperately tried to break free upon hearing the sirens, but the men kept their promise, and the entire crew sailed safely through danger. They all worked together to strategically prevent their own demise.

The lure and noise of the financial media often drive the behaviors and decisions of investors. A Ulysses Pact is like an investment policy statement, a proactive and strategic agreement that is made between a client and advisor. An advisor can guide clients through the murky or turbulent waters and ensure they don’t jump ship in response to the noise by signing a Ulysses Pact. This pact allows investors to agree up front that they will not act on emotions that can lead to irrational and wealth-destroying decisions. It can serve as a promise to one’s future self to follow a passive advisor’s counsel to hold on and not buy or sell as a reflexive reaction to the short-term gyrations of the market.

The Siren Songs of Speculation

The Siren Songs of Speculation

The lure and noise of the financial media often drive the behaviors and decisions of investors. A Ulysses Pact is like an investment policy statement, a proactive and strategic agreement that is made between a client and advisor. An advisor can guide clients through the murky or turbulent waters and ensure they don’t jump ship in response to the noise by signing a Ulysses Pact. This pact allows investors to agree up front that they will not act on emotions that can lead to irrational and wealth-destroying decisions. It can serve as a promise to one’s future self to follow a passive advisor’s counsel to hold on and not buy or sell as a reflexive reaction to the short-term gyrations of the market.

Renowned investor Warren Buffett is an advocate of index investing. In his 2017 letter to shareholders, Buffett stated it plainly: “The bottom line: When trillions of dollars are managed by Wall Streeters charging high fees, it will usually be the managers who reap outsized profits, not the clients. Both large and small investors should stick with low-cost index funds.”

Buffett’s heirs will benefit from this advice, as well. His 2014 letter states that he has directed the trustee of his sizeable inheritance to invest in two straightforward investment vehicles: 10% is to go into short-term government bonds, and the 90% balance to be invested in index funds.9 Buffett’s affinity for indexing is not new. For many years, he has recommended index investing in several of his letters to shareholders. In his 2004 letter, Buffett stated that “Over [the past] 35 years, American business has delivered terrific results. It should therefore have been easy for investors to earn juicy returns: All they had to do was piggyback corporate America in a diversified, lower-expense way. An index fund they never touched would have done the job. Instead, many investors have had experiences ranging from mediocre to disastrous.”10

Buffett not only advocates index funds, he’s betting on them. The June 2008 issue of Fortune11 Magazine reported that Buffett wagered a million dollars that an S&P 500 index fund’s ensuing 10-year returns would beat those of five actively managed funds or hedge funds chosen by Protege Partners, a prominent New York-based asset management firm. Citing the Wall Street Journal, Buffet’s hand picked S&P 500 index fund compounded an annual return of 7.1% compared to the basket of funds selected by Protégé Partners, which returned 2.1% from January 2008 through December 2017. An interesting note, Protégé Partners hedge fund manager Ted Seides, who accepted the wager with Warren Buffett, admitted defeat almost eight months in advance of the December 31, 2017 end date.

Many highly respected financial experts share Buffett’s enthusiasm for index funds. In his book, Charles Schwab’s Guide to Financial Independence, Schwab revealed, “Most of the mutual fund investments I have are index funds, approximately 75%.”12

Benjamin Graham, influential economist and mentor to Warren Buffett, spent most of his professional life analyzing companies for stock market bargains. However, shortly before his death in 1976, Graham rejected his previous beliefs, stating that he is “…on the side of ‘efficient market’ school of thought now generally accepted by the professors.” Graham was a visionary in his early description of what is now known as value index investing.

Noteworthy institutional investors also advocate index funds investing. David Swensen, Chief Investment Officer of the highly successful Yale Endowment Fund and author of Unconventional Success: A Fundamental Approach to Personal Investment13 and Pioneering Portfolio Management: An Unconventional Approach to Institutional Investment,14 has been particularly outspoken about the merits of index investing for individual and institutional investors alike. In an August 2011 article which appeared in the New York Times, Swensen blasted active investing and its facilitators, including mutual fund companies, retail brokers and advisors. He said that market volatility causes ill-advised investors to behave “in a perverse fashion, selling low after having bought high.” He asks, “What should be done? First, individual investors should take control of their financial destinies, educate themselves, avoid sales pitches, and invest in a well-diversified portfolio of low-cost index funds.”15

Bear the Risk

Bear the Risk

So what is the lesson here? Like the illustration on the following page titled Bear the Risk, when you fully embrace a new way of investing, you can substantially reduce the stress and anxiety commonly experienced by active investors. You should be calmer, relaxed and more centered in the midst of the noise and frenzy of media pundits and Wall Street. An unwavering commitment to your investment plan should allow you to let go of unnecessary worry and enable you to focus on what truly matters to you most. You should not only be rewarded emotionally, but you will also improve your probability of investment success. Why would you want to do anything else?